- Home

- Robert Louis Peters

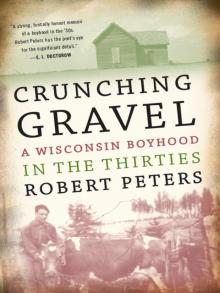

Crunching Gravel

Crunching Gravel Read online

Crunching Gravel

A Wisconsin Boyhood

in the Thirties

Robert Peters

The University of Wisconsin Press

A North Coast Book

CONTENTS

Title

Copyrights

Dedications

Series

Crunching Gravel

Part One: Winter

Part Two: Spring

Part Three: Summer

Part Four: Fall

The University of Wisconsin Press

1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor

Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059

uwpress.wisc.edu

3 Henrietta Street

London WC2E 8LU, England

eurospanbookstore.com

Copyright © 1988,1993 by Robert Peters

The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embeddded in critical articles and reviews.

Printed in the United States of America

Originally published in the United States by Mercury House, San Francisco, California. Earlier versions of “The Butchering” and “The Sow’s Head” appeared in The Sow’s Head and Other Poems (Wayne State University Press, 1968) and Gauguin’s Chair: Selected Poems 1967-1974 (Crossing Press, 1977). A chapter from “Winter” appeared in Margin (London, 1986). “Albert,” “Rumors of War,” and “Halloween” appeared in Zyzzyva (San Francisco, 1988).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Peters, Robert, 1924–

Crunching gravel : a Wisconsin boyhood in the thirties /

Robert Peters.

128 p. cm.

ISBN 0-299-14100-4 ISBN 0-299-14104-7 (pbk.)

Originally published: San Francisco: Mercury House, c 1988.

1. Peters, Robert, 1924– —Childhood and Youth.

2. Poets, American—20th century—Biography.

3. Wisconsin—Social life and customs. 4. Farm life—

Wisconsin. I. Title.

PS3566.E756Z463 1993

811'.54—dc 20 93-19801

ISBN-13: 978-0-299-14104-2 (pbk: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-299-14103-5 (ebook)

For my children,

Rob, Meredith, Richard, and Jefferson,

and for my sisters,

Nell, Marge, and Jane

Blueberries, blueberries, fish and venison. That’s what we lived on. But the air was good, though a bit damp and arthuritical in them long winters. You could never heat the house. Near the stove it was so hot you couldn’t sit there; yet when you moved away, your back froze. And the floors was always like ice. Your toes warmed up only when you put ‘em in hot water or was in bed with quilts heaped over you. Yes, I’d live no place else.

—Charlie Carlson, farmer, bachelor

I remember Bobbie Peters. Sure. He was a baby when he came to my first-grade class. He was three, was potty-trained, and could read all the first-grade books. He’d taught himself by copying ABCs off those cards that came in shredded wheat packages, dividing the biscuit rows. He filled up any paper he found. To show what he’d done, his mother brought cutup brown paper sacks to show his good printing. We let him enter first grade, although he was only three. I helped him write poems and stories. He could never catch a ball, cried a lot, and hung on me too much. I saw him through eighth grade. He’s turned into a writer, I hear. That’s nice. I still picture him, aged five, standing in front of my desk, holding out yet another of his little stories about some cute animals, Cubby Bear and his friends.

D. C.

Bob was bright, though shy, their being so poor and all. If you lived in the sticks you were lice on a pig’s behind. All the roads were covered with gravel—no blacktop then. And your shoes crunched walking on it. You had to live in town with plumbing, running water, and electric light to count for much. I loaned Bob a suit of mine (although he was only fourteen, he was my size, 6’3”) so he could represent the school in forensics. I guess I was wrong. He stood on that stage in Marshfield, started off good, saw me in the audience, and forgot his lines.

—E. V. Kracht, high school principal

I went there to be a lumberjack. But the big timber companies had cut everything down. You had to go way up to the Porcupines in upper Michigan if you aimed to be part of any frontier. I just settled on forty acres in the sticks, and grubbed along raising pigs, chickens, cows, kids, and taters. Sure I wanted more.

—Herb Jolly, farmer

Crunching Gravel

A Wisconsin Boyhood

in the Thirties

Part One: Winter

Snowscape

The storm had piled up a good foot of snow, obliterating the road leading to town. The wind whipped drifts, piling them against the house so that we had to force the kitchen door open. Mounds and hillocks were covered with ice-glaze. Birch and poplar trees were ice-coated; each twig struck by the dazzling sun shimmered. Trees swooped to the ground, so laden with ice their shapes were forever contorted.

To reach the barn, you had to plant each rubber-booted foot slowly, breaking through the glaze to the buried path. A sift of chickadees swept down to eat the seeds of a clump of goldenrod, scattering almost as soon as they landed. The icy air bit your lungs. Your cheeks tingled. The dog stirred from his house. His face was rime white.

Flaring tamarack, pine, and spruce, showing their undersides of green, were perfect mounds of snow, contained, unsullied. Over their tops, distant Minnow Lake glinted with sun, yet another white expanse in this frozen Eden. White smoke drifted from the tin stovepipe secured with baling wire to the roof The snow had begun to melt around the pipe. You grabbed the nearest birch sapling and shook it, loving the sounds of the cracking ice shattering from the branches.

Accident, Fear

At 1 A.M. the moonlight was so brilliant you could read by it. The fields were still ice-choked, intensifying the light. Only that morning the county plow had cleared the road leading to town. I was eleven and sat on my bed gazing out the upstairs window at the fields and the glorious night. Dad was in town seeing a friend, playing music. “Look after Mom,” he had said. “You’re in charge.” I took the responsibility seriously and slept poorly throughout the early part of the night.

The combination of highland air, chilled temperatures, and resonant ice and snow amplified sound. The roof boards snapped so loudly I was sure a raccoon or a skunk was up there. The hum of an approaching car built slowly. Weak, jiggling headlights shone. Suddenly, opposite our house, the car, a Model A Ford, spun out of control and flipped over on its top, landing halfway up a large drift. The wheels kept spinning.

I ran downstairs to the kitchen where my mother was watching through the window. The door was locked.

“He’s coming here,” Mom said.

The driver had worked himself free from the wreck and was weaving up the hill.

“Who is he? Who is he?” I whispered.

“I’ve never seen him,” Mom said, pulling me to a corner.

“He’s probably drunk.”

“Hey, hey,” the man called, pounding on the door. “Anybody home?” Silence. More pounding.

“What if he’s hurt?”

“Sh. Sh. If he’s drunk, he might kill us.”

My dad’s guns were in the bedroom, useless since I’d never fired them. Sweat dampened my neck.

The man was in his twenties, husky. We knew everybody living in S

undsteen. We didn’t know him. He returned to his car and somehow righted it, maneuvering into the road. He drove off.

The episode lingered like the taste of zinc. I was too frightened to open the door. I had failed. The code said to help anyone in need. I had rationalized, saying I had spared Mom. What if the man was drunk? We never found out who he was. Dad said he was glad I hadn’t opened the door. “Nobody’s within earshot if you’d needed help. You did right.”

Mother

Dorothy Keck Peters (1906-1980) was born near Grand Forks, North Dakota. She was the eighth of ten children, five sons and five daughters. Her mother’s family, the Haverlands, was English and her father’s family was German. When she was in her early teens, her father was gored by a bull. He lingered in great pain and died. His sons kept the farm running.

My parents’ marriage was a mix of love and convenience. Mom’s mother had insisted that she either marry or get a job in town, for she could no longer live at home. She was taller than most women, slender, with luxuriant black hair that began to gray before she was thirty. She was immaculate. Although she was poorly educated she had completed a year of high school in Grand Forks—she believed in education. In 1923, when she was sixteen, she met Sam Peters, an itinerant member of the seasonal threshing crew. He was twenty.

That September they married and drove in a Model T Ford to Wisconsin, where Sam’s brother Geshom (“Pete”) was settled. My mother was soon pregnant, which did little to still her loneliness, dumped as she was into extreme isolation three miles from the nearest town, Eagle River. Her sister-in-law lived nearby, but Kate was strange. This French Canadian woman was superstitious, had sent an old man to prison for ostensibly raping her, had an illegitimate son who shot himself when he was twenty-one, and gave the illusion of awesome powers. My mother, for self-protection, saw as little of her as possible.

My father worked in town as a mechanic, which meant that my mother was alone much of the time. The house, built of heavy hewn logs cut by my dad’s father, Richard, was utterly primitive. There was an outhouse, and water had to be pumped outside. My mother, hardly more than a girl, worried that a doctor would not be available when she needed him. A month after her seventeenth birthday, I was born. She named me after Robert Louis Stevenson. A Child’s Garden of Verses was the only book we owned.

Watering the Cows

At 4:30 P.M. the school bus dropped me off. It was already dark. I wrapped my muffler around my face and rushed to the house. The shed windows were already frosted. Icicles four foot long hung beside the door. Wisps of smoke floated from the metal chimney pipes. The roof snapped and cracked under its burden of snow, on this, one of the coldest days of winter.

I hastily changed my wool slacks for overalls. Each lost minute would make watering the cows more difficult. The pump would be frozen, and the cow and her bull calf would be incredibly thirsty—they hadn’t had water for twenty-four hours.

I grabbed a hot water kettle and hurried to the pump. The handle resisted at first. I grabbed a half-barrel, freed the bottom of ice by kicking it, and shoved it under the spout. Steaming water spewed forth.

Lady pulled free of her chain, dashed off a few yards into deep snow, wallowed, pulled free, returned to the path and waited for her calf As she drank, her head was lost in steaming, freezing air. When she was sated, I emptied the tub, and turned it over in case of heavy snow.

Returning to the barn, I forked timothy and clover. As the cattle ate, I shoveled manure through a trap door, cleaning the stalls by lantern light. I secured the animals and returned to the house. In another hour and a half I would milk Lady.

In the living room, I crowded near the potbellied stove. The sides were red-hot. Pitch pine was burning. Pine takes fire the moment a match touches it. I brought the kerosene lamp to the table’s edge. Holding my Latin book near the lamp, I read the new declension. I would review it several times before supper and again later while I milked. By bedtime—about 8:30—I’d have it memorized. In the morning I’d brush up on the way to school. There was also algebra, which gave me trouble. Most nights I finished about half the math homework. The ruthless logical relations of parts drove me crazy. I felt stupid, so I took as much math as I could. My report card showed As in other subjects, while math hovered at C.

After a supper of potatoes and eggs fried in bacon grease, tinned Argentine beef, courtesy of County Welfare, dill pickles made by my mother, canned green beans, and bread and butter, I returned to the barn. I wiped Lady’s udder, then began the slow-pressured squeeze. I loved the sound of milk striking metal—like tiny explosions blended with shredding silk. The gray cat sat nearby. When the pail was nearly filled, I stripped the teats; then I checked to be sure that Lady had bedding, and I extinguished the lantern.

The stars were close enough to touch. The horizon shimmered with northern light. No wind. Land and trees suspended in crystal—the advent of an extreme chill. Inside their shed the pigs whiffled. Not a sound came from the henhouse. Later, my dad would start a fire in the gas-tank heater. On such brilliant nights my usual fear of the dark eased—no wolves, bear, or wild men of the woods would sally forth in such cold. The light from the living room window, though feebly cast, was magnified in the subarctic air. It fell over the snow at my feet like daffodils.

The House

Built of logs and axe-hewn beams, our new house sat on a knoll flanked by white birch, Norway pine, and spruce. It looked thrown together as if by a troll—the hip-roofed upper storey, with its tiny cross-paned window facing the gravel road, was askew. The surface plaster was a dismal gray. The northern hip was longer than the southern. And the weathered clapboards were badly chinked with moss and plaster. From the roof emerged a thin blue tin stovepipe, anchored to the roof with baling wire. As if the soot were burning, sparks flew, expiring on the snow.

The lower storey fit snugly into a tree-covered hill complete with a root cellar. An unpainted gray clapboard shed, jerry-built, was affixed to the lower storey, as a kitchen and storage room for mops, pails, and winter clothing. The stoop, which my mother kept brushed clean, was of cheap pine boards painted blue. All around the house, from the eaves, hung long icicles, some as tall as a boy.

Beside the cardboard-insulated door, the snow was stained where we relieved ourselves in cold weather. In spring, the weeds were luxuriant, for we also dumped dishwater there. Nearby, bared to the elements, was a small green pitcher pump, the source of our water. Beneath a wooden platform, layers of straw protected the pump from freezing.

Fronting the house was an area fenced with wire, holding dead bachelor’s buttons and withered cornstalks. Beyond, snow-piled, was a three-acre field for potatoes, cabbage, turnips, onions, and strawberries. A shoveled path led down a short incline to the graveled Sundsteen Road. Snow banks were shoulder-high, with excavations hollowed out as ice caves by my sister and me. Our mailbox, with its red metal flag, was across the road, set for easy access by the mailman, Francis Sailer.

We could see the Kula farm. Mrs. Kula labored in the fields and spoke only Polish. She always wore a white babushka. Her husband was a hard-working man of great rages who cursed both sons and horses. The Kulas made little effort to fit American ways; they might just as well have been tilling fields near Kraków.

Doing the Wash

On the night before we washed clothes I filled two galvanized rinse tubs and set them in the unheated outer shed attached to the kitchen. In the morning we would have to remove the layer of ice formed during the night. We ladled hot water from a copper boiler into a primitive hand-crank washing machine. My job was to work the agitator. We started off with all the whites, squeezing them by hand into the first rinse, prepared with blueing, and then a second rinse. Mom and I took turns hanging the clothes outside; it was my chore to shovel snow from beneath the lines. In a few minutes, even if you wore gloves, the dampness from the wash froze your fingers, and you had to go inside to warm them. Soon we were finished, and the clothes on the line were board-stiff The sh

eets we dried in the kitchen and living room on rope strung up for the purpose. I loved the fragrance of fresh starch in the antiseptic frigid air. Years later, my mother blamed these conditions for her arthritis.

Movies

The Saturday before Christmas, Dad gave my sister Margie and me a quarter apiece for a matinee. It would be dark when we got out after the double feature. The weather was cold and clear. “Walk fast and you’ll stay warm,” Dad said. I had never before seen a movie.

We arrived just as the first film began and found our seats in the dark. The credits appeared: Rose Marie, starring Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy. I believed every moment. I knew that Jeanette could position herself on a real Rocky Mountain peak on a moonlit night, warble “Indian Love Call” across the intervening canyons, and be heard by Nelson Eddy, clad in his Canadian Mountie uniform, seated on yet another peak listening and returning the song. MacDonald was an apparition made filmy and mystical via the soft-focus effect of the camera’s lens. And how I wished that Eddy were my father leading that cadre of Royal Mounties in immaculate close-order drill through the vastness of those mountains.

The second film was a shocker, an exploitation film on the Ku Klux Klan and the lynchings, torturings, and burnings of southern blacks. I had been only dimly aware of that vicious social history.

I left the theater dazed and took Margie’s hand as we walked through the town toward Sundsteen Road. It was already dark, and a soft drift of new snow was falling. I loved the play of the flakes in the arc of dim light around the street lamps.

Crunching Gravel

Crunching Gravel